After the last slaves have been ripped off to the sinister Power that represents for the black people the course of color,the slow 300-year-old stratification of captivity, it is, despotism, superstition and ignorance, will need to be subdued by means of a virile and serious education.

— Joaquim Nabuco, “O abolicionismo”, 1883

The 19th century started off with promises of insertion of the recently independent Brazilian nation on the list of the so-called civilized nations, which followed European standards of political and social organization. There was a court, an emperor, a constitution, museums, libraries, colleges and… slaves.

Even with the strong pressure by Great-Britain, which saw the maintenance of a slavery regime backwardly in a humanitarian and economical point of view given the logic of the rising industrial capitalism, the fact is that both traffickers and landowners kept the system working for as long as they could. Some measures were taken to try and placate the British pressure – “coisas para inglês ver (things for the English to see)” – such as the gradual prohibition of the black people trafficking, initially in 1891 (with no practical effect) and then in 1850 (with the Euzébio de Queiroz Law)

On the other hand, legislators, ministers, noble men – in their majority enslavers – feared that something similar to what had happened decades before in Haiti (the slaves grouped together and proclaimed the independence of the country, expelling the French settlers) would happen here. The fear of that event haunted and motivated some concessions such as the permissiveness, with which the slaves crowned the king of Congo in the Neutral Municipality. They’d rather let them crown their king with merriment than having him removed from the throne.

The emergent abolitionist movement – from 1850’s onwards – played a leading political role. Intellectuals and politicians alike became engaged, especially through the written press, in the abolition cause.

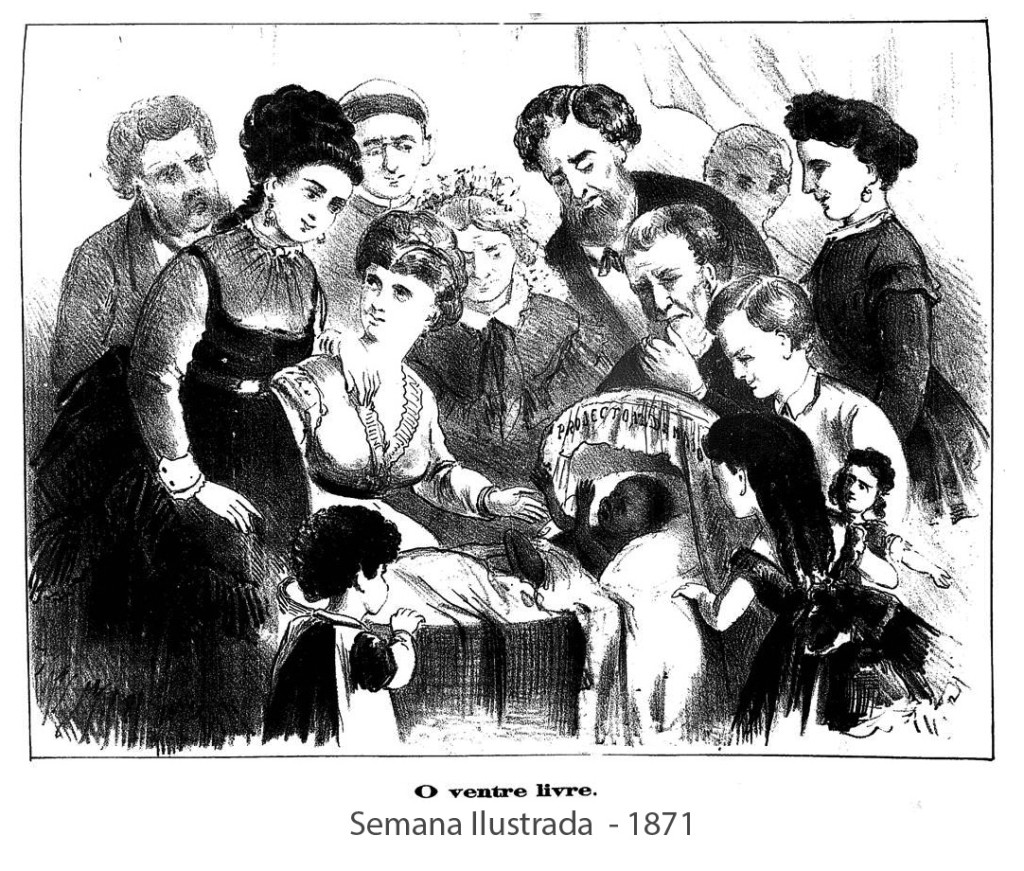

Joaquim Nabuco, André Rebouças, Luiz Gama, Castro Alves were staunch militants. They articulated in the press and in the parliament, resulting in gradual achievements, among them the “Lei do Ventre Livre” (Free Womb Law) in 1871.

According to this law, from 28 September 1871 onwards, every child born from a slave mother would be free. The law, however, imposed limitations: this child – from then on called naïve as he or she did not know the evils of slavery – would remain under custody of his or her mother’s owner. As a free child, they were not allowed to do any sort of job until turning eight years of age. From then on, the child would be allowed to remain next to their mother until turning 21 at their owner’s will, paying for food and shelter with labour. On the contrary, he or she would be handed in to the care of the state upon indemnity.

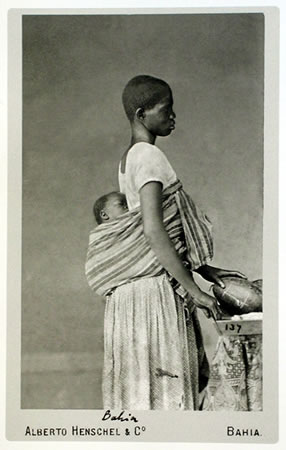

In practice, less than 1% of the children were delivered, which can be understood not only as the permanence of the slave condition, but also as an achievement of the slaves, since the separation from their children could lead to even more discontent and insubordination. Since the abolition was inevitable, it should at least take place in a lethargic pace without great ruptures.

It is interesting to notice that the same movement that discussed the condition of the child born from a slave mother did so with the childhood. In this period, many guide books regarding orphans were published intending to civilize the country. Regarding the discourse on childhood, to civilize meant to put order, to separate the wheat from the chaff. As for the indigenous children, they took up an assimilationist approach: at the so-called houses of craftsmanship, a profession would be taught so that the children could be integrated into and useful to society. The orphans and the naïves would be treated likewise.

The discourse on the childhood attributed a specific place to every child: the poor, impaired, exposed or naïve went to the orphan colonies, homes and companies of sailor apprentices so as not to become vagabonds. The heirs of the rising republic in the end of the century, however, were expected to be enrolled in kindergartens and enjoy an effulgent and happy future.

The fourth chapter of The Childhood of Brazil by José Aguiar was inspired in a criminal process, which took place in 1881, Uberaba, Minas Gerais. In this report; which portrays the hesitation involving abolition and the protectionism, with which state institutions have been treating the elite; a naïve named Alexandrina denounces her mother’s owner’s son for mistreating her. She was a victim of aggression for not having managed to properly clean the house courtyard. On the other hand, the lady claims that the girl stole money. The sheriff registers that the girl was “seven to eight years old”, which makes it hard to precise her age. If she were under eight, she was not supposed to be working. In this case, the girl is acquitted not only for being a child, but also for coming from a slavery background.

—Claudia Regina Baukat Silveira Moreira is graduated and has a masters in History at Universidade Federal do Paraná. Nowadays, she is professor at Universidade Positivo and is doing her PhD in Educational Policies in the Post-Graduation Program in Education at Universidade Federal do Paraná.