“(…)

Work ennobles and seduces,

It makes our souls hover in the heights,

He who works sows in a land,

Which gives us strong ripe harvests!

Work is duty which imposes itself,

Both to the rich whose luck incites,

And to the poor man who fights without truce,

In the hardest and exhausting combat— José Rangel and Duque Bicalho, Excerpt from “Canção do trabalho” (Labour Song), 1932

The Revolution of 1930, leaded by Getúlio Vargas, besides ending with the Old Republic (characterised by liberalism in the economic field combined with regime ruled by colonels in the political field), opened doors to what later became known as the Vargas Era, which lasted until 1945. In its 15 years of existence, there was a great change in the economical profile of the country and substantial changes both in the international affairs and in the domestic politics.

Under the state’s baton, the country became industrialised, motivated also by the need to replace importation, since the European and North-American industry were focusing their efforts on the production of arms during the Second World War (1939-1945). Adding to the pioneering sectors such as the weaving and food industries, an industrial park was installed. Thus, the Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional, the Companhia Vale do Rio Doce, and the Companhia Hidrelétrica do São Francisco were created, such enterprises were seen as catalysts of a policy aiming at the industrial development in a country that was becoming modernised and urbanised, induced by the end of the coffee economical cycle.

The urban worker emerges as a new social person who deserves attention. From this social segment in particular the regime receives political support by means of constant effective actions and a lot of advertising. In the action plan, the Vargas government, besides assuring the access to work through industrial policies, also implemented interventionist measures which began to grant right to workers: minimum wages, working hours and paid holidays are examples of innovations that transformed the Brazilian State into an arbitrator between the capital and the work.

At the same time, the legislation that guaranteed new rights, set boundaries to the organization of workers. Unions, in order to be acknowledged, needed to bend to some rules, being at the mercy of the state.

Operating in a populist way – it is, acknowledging the rights, but turning the population dependent on the state – vargismo (period when Getulio Vargas governed the country) mirrored totalitarian regimes such as those emerging in Europe at the same time. The actions and the speeches addressed the “workers of Brazil” that should make an effort to help the country develop. In this sense, the celebration of the International Worker’s Day – 1st of May – was given a civic status, involving great festivities and parades, with songs such as what are to be found in the epigraph above.

On the radios, national values and culture were give strong expression either through musical programmes or through the “Hora do Brasil – Hour of Brazil”, a daily radio programme produced by the Department of Press and Advertisement, responsible for spreading the news on the deeds of the government. The samba, which became a national symbol of the nation, started being exported as a synonym for the Brazilian exoticism.

It did not take long for the cultural industry and the American diplomacy to see in this manifestations an opportunity from both political and economical points of view. Among the efforts in the Second World War, the so-called Good Neighborhood Policy aimed at co-opting South American countries. In order to do so, besides political and economical arguments, it was necessary to conquer the hearts and minds of the common citizens. The cinema industry of Hollywood was heavily used to mobilize the population.

Carmen Miranda was the main ambassadress of this exotic and warm Brazil. Multi-artist, she understood like only a few the convergence of talents demanded by the cinema industry.

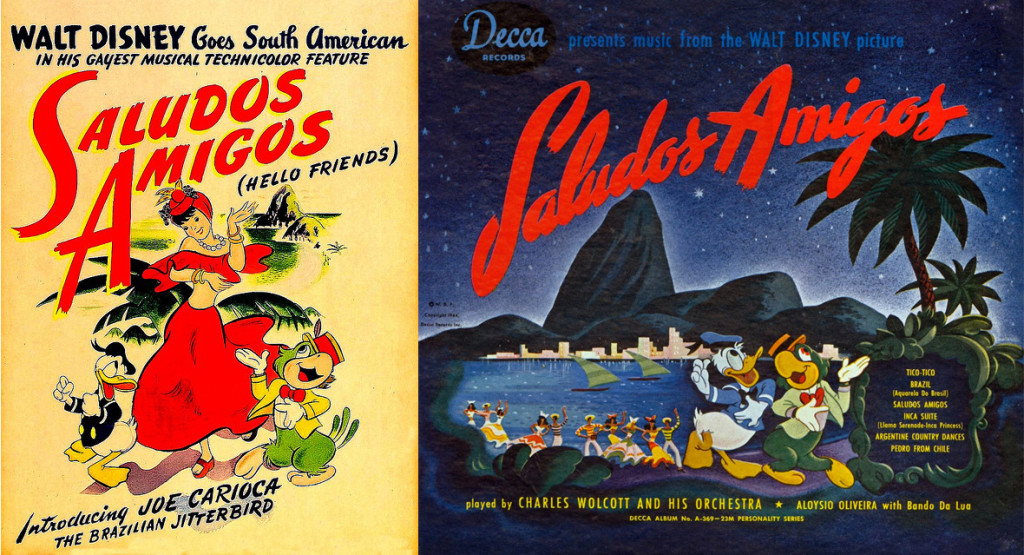

In a trip in South America, Walt Disney created a few animations such as “Saludos Amigos” and “The Three Caballeros”, in which exoticism and, above all, the United States’ approach to Brazil became highlighted.

It explains, to some extent, the political choice made by the Vargas’ regime in favor to the Allies, even though his government had some fascist inclinations on the domestic field. The Brazilian position, however, remained neutral as long as possible, motivated specially by economical needs, since the commercial relations of Brazil with Germany and the United States had the same weight.

The fifth chapter of “The Childhood of Brazil” approaches this rich period in the Brazilian history, capturing scenes of a contradictory society, which sways between the modern and the archaic. It is a society that oscillates between the protection of the childhood and their education to become workers. It is a country that shows itself dictatorial to its own citizens and at the same time engages in the Second World War. With no intention of being didactical, comic artist José Aguiar, prioritizes the contrasts between the daily work and the charm given by the cinema from the perspective of a mother and her two sons.

—Claudia Regina Baukat Silveira Moreira is graduated and has a masters in History at Universidade Federal do Paraná. Nowadays, she is professor at Universidade Positivo and is doing her PhD in Educational Policies in the Post-Graduation Program in Education at Universidade Federal do Paraná.