“The day greatest captain Pedro Álvares Cabral lifted the cross (…) it was on the third of May, when the Santa Cruz invention is celebrated in which Christ Our Redeemer died for us and for many years was known for its name. However, since the demon with the sign of the cross lost all power he had over men, fearing also to lose the power over those of this land, he strove so people would forget the first name and maintained the name of Brazil, which is called this way due to a red and scorched coloured wood with which cloths are dyed and gave ink and virtue to all church’s sacraments.

—Frei Vicente do Salvador, 1627.

Paradise or hell? This tension is the mark of the European occupation of American lands, particularly Terra brasilis. Together with reports that “all that was planted grew” or that the nudity of Indians would be the proof that one had found the lost Eden. There also used to be moral condemnation of traditional practices, especially anthropophagy. This debate permeated during the whole of the sixteenth century, opposing names such as Bartolomé de Las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda. The first, a Dominican who lived amongst the native people of Central America and defended the autonomy of the people of the New World, the latter, a theologian who defended the right of the Spanish Empire to enslave them. The thesis of the European supremacy won, generating the colonization, which, in turn, was truly a hell for many.

The first decades of colonization of the Americas are depicted in the film “1492: Conquest of Paradise”. France/Spain, 1992. Directed by Ridley Scott.

Europe was beginning to leave the Middle Ages behind, but its people had still not completely awakened. The Protestant Reform shook the structures of power and the Catholic reaction accompanied the adventurers who were looking for new markets to enrich the rising mercantile capitalism.

So, together with the newly created Modern National States, there was the need to find lands to explore metals and precious gems (as well as other potential richness) and expand their territories.

Our colonization was predominantly masculine: explorers, merchants, Jesuits. There was no project to constitute something that resembled a civilization. A colonial pact imposed a regime that forbade the installation of a manufacturing industry. This situation dragged itself on up to 1808, when the royal family moved to Rio de Janeiro. Apart from the explorers and the merchants arriving with the clear purpose of becoming rich, there were the disgraced ones who had traded their jail sentences for a risky trip, where death crept in. There were also explorers from other nationalities such as the French and the Dutch who tried to usurp Lusitanian lands.

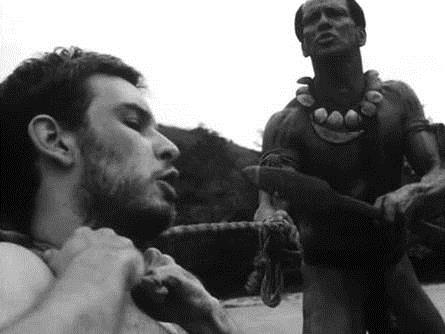

The story of German sailor Hans Staden, who was twice in Brazil during the sixteenth century is a proof of that. The movie “Hans Staden” (Brazil/Portugal, 1999. Directed by Luiz Alberto Pereira) depicts this story.

In Santa Fe, it was imperative to win the dispute with the Protestants. It was a true war in the name of faith. It became rather convenient to create a religious organisation inspired in the military: The Corporation of Jesus.

On the one hand, the state was lethargic in its action, on the other hand, however, the Jesuits were extremely efficient with their strategy. They founded villages and schools, always with the purpose of converting the highest number possible of souls to the “true faith”. They took care of the souls and lives of settlers as well as natives. They used to take care of the moral conduct of all, condemning the sexual intercourse between Portuguese and Indians, promoting marriages between the first and the so-called “orphans girls of the king”, who were usually left to their own devices and imported to satisfy the settlers’ sexual appetite as means of restraining crossbreeding. They were monitored and extensively protected during the ocean crossing as they were to be kept virgin till their wedding.

Although it is a fictional piece of art, “Desmundo” (Brazil, 2002. Directed by Alain Fresnot) highlights important elements in that period: the importation of orphan girls and the trade including with the Indians. It is the adaptation of the homonymous romance of Ana Miranda.

Just as impossible it was to refrain from the sexual desire and the crossbreeding, it was also impossible to frame the costumes into religious canons. So, apart from the challenges imposed to those who wanted to convert the black people of the land, a popular Catholicism existed, which ignored the religious canon. The magical and the religious merged in it, opening ground to all sorts of rituals. The birth was one of these key movements, in which protection coming from the skies was required. Protection against the evil was necessary. After all, the devil was always peeping.

The children of settlers – be them mixed race, be them kids of Portuguese parents – were born surrounded by rituals. The recently born baby from a white family was immediately bathed in wine or cachaça, cleaned with butter or oils and then firmly swaddled. Castor oil was used in the belly button. Dirtiness was considered powerful remedies against the evil eye. The same way, the umbilical cord and the nails were buried in the garden as means of stopping them from being used in witchcraft.

It was a relief when the mother and the baby survived the birth, given that the beginning of life was haunted by death. The low life expectancy at birth – 50% of the children died before reaching the age of seven – led people to detachment. The childhood was seen as a passage, which it was necessary to survive. Adults, especially women, were responsible for taking care of this period. However, it was always necessary to be ready for the high mortality. Women counted the number of their kids they gave birth to, alive and dead: “four male, two female and three little angels”. Children were compared to things as means of minimising the suffering that loss sparkled.

This is the environment in which the first chapter of “The Childhood of Brazil” be José Aguiar is set. It was moment of shock between civilizations and worldviews. It was also the moment of the birth of our nation, however questionable and symbolic it may have been.

—Claudia Regina Baukat Silveira Moreira is graduated and has a masters in History at Universidade Federal do Paraná. Nowadays, she is professor at Universidade Positivo and is doing her PhD in Educational Policies in the Post-Graduation Program in Education at Universidade Federal do Paraná.